Drawing. Conclusions

I started writing this over a year ago.

I loathe the vast majority of imagery generated by AI. There are some exceptions but they’re notable by their scarcity.

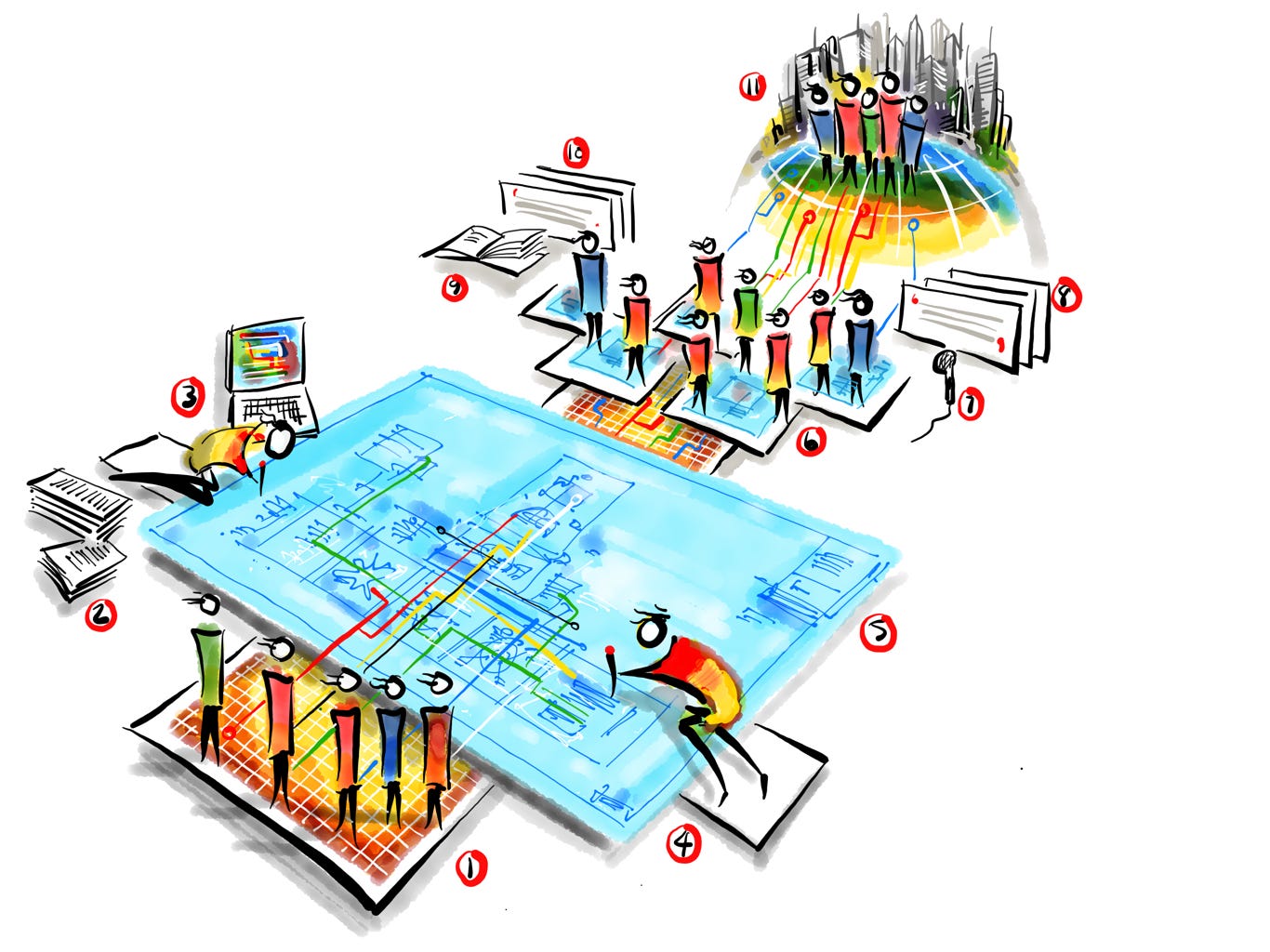

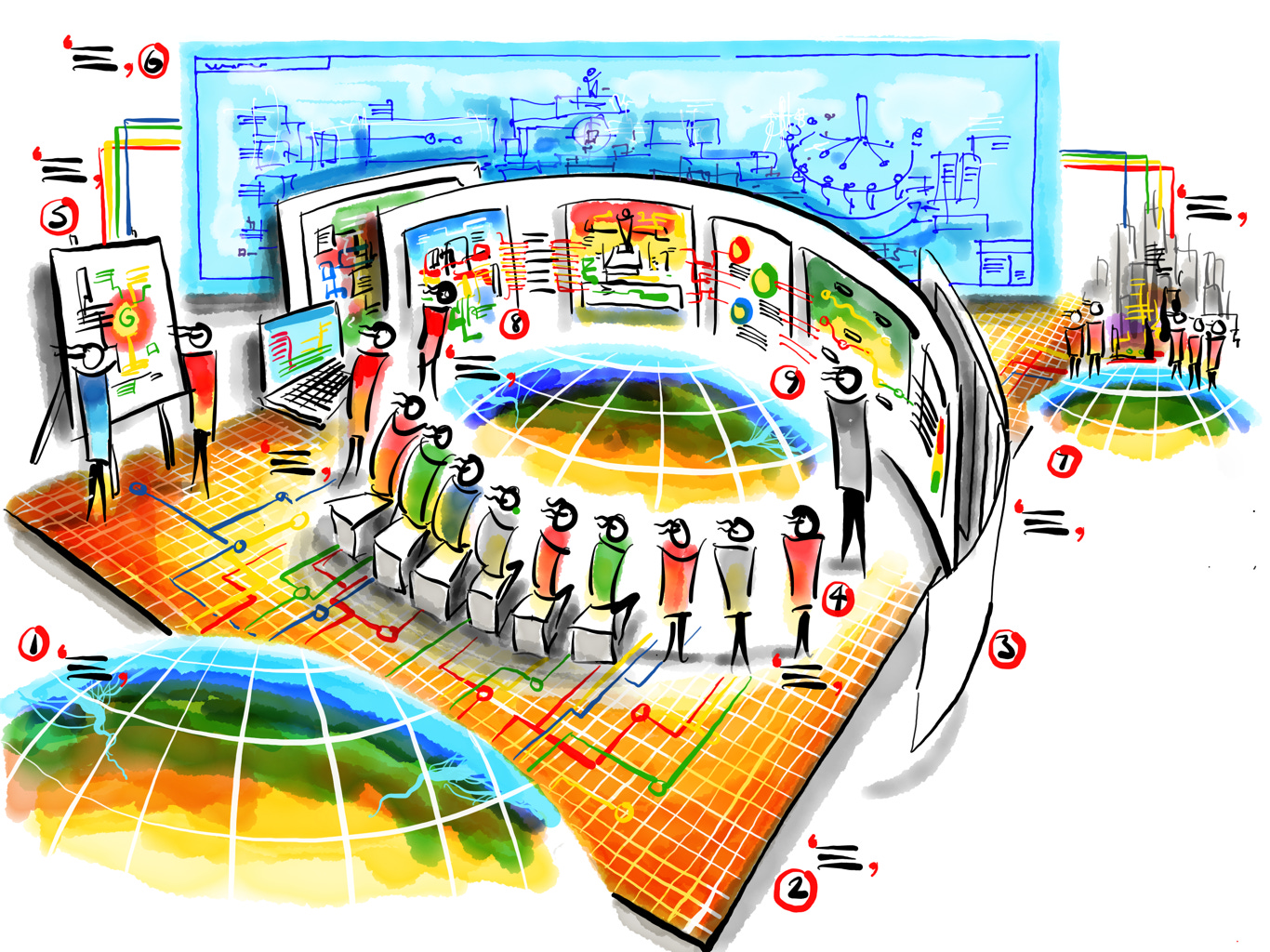

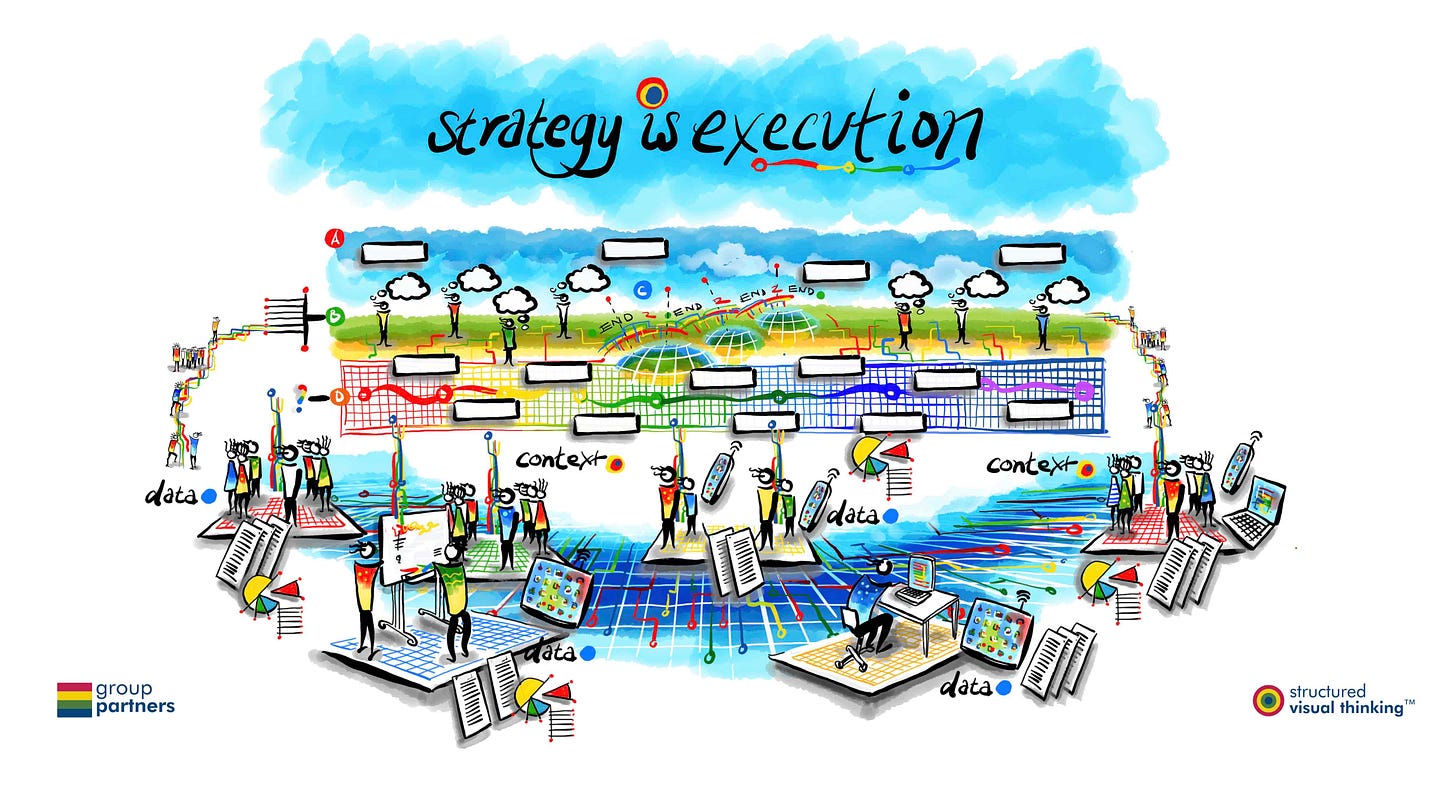

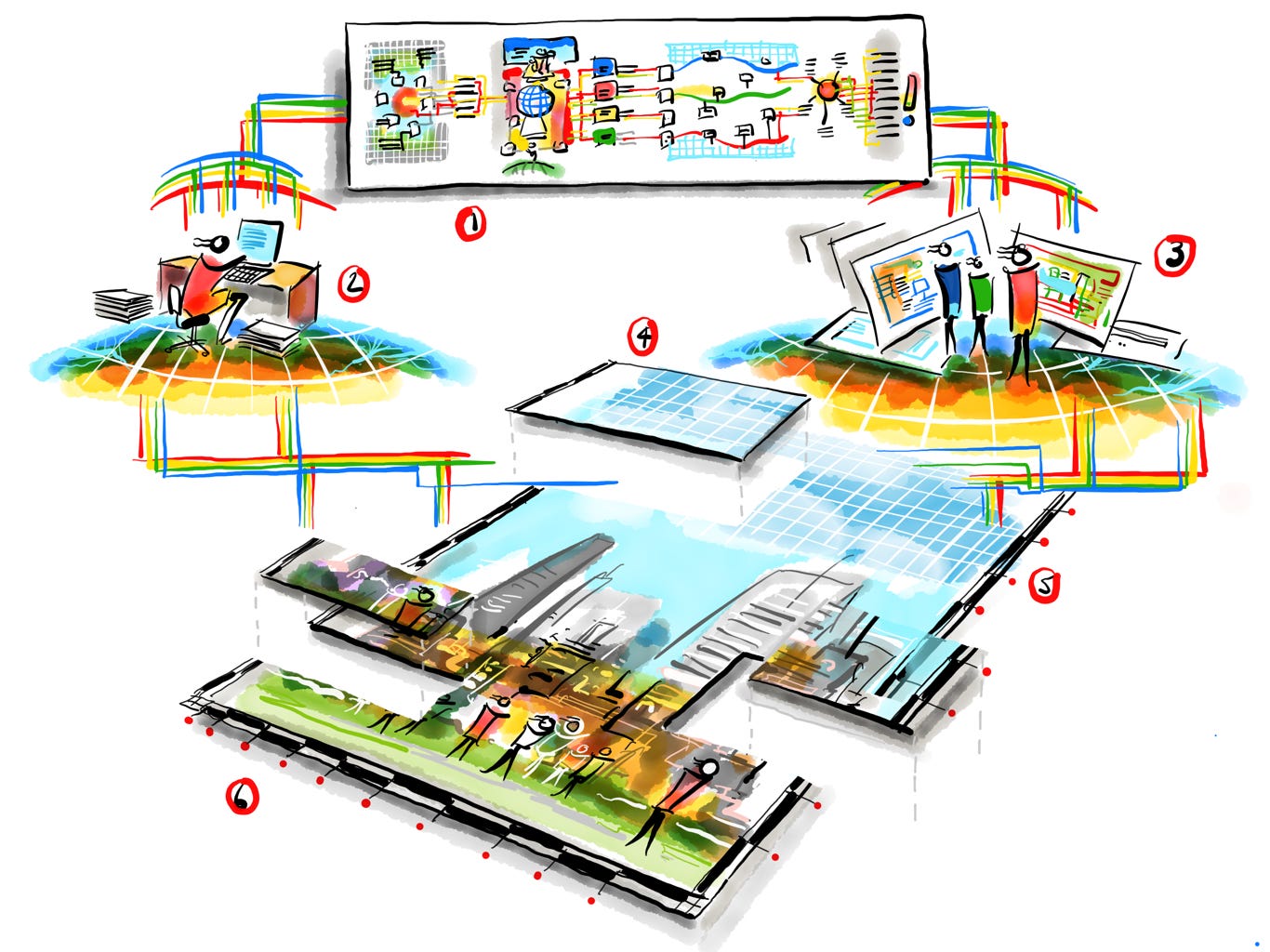

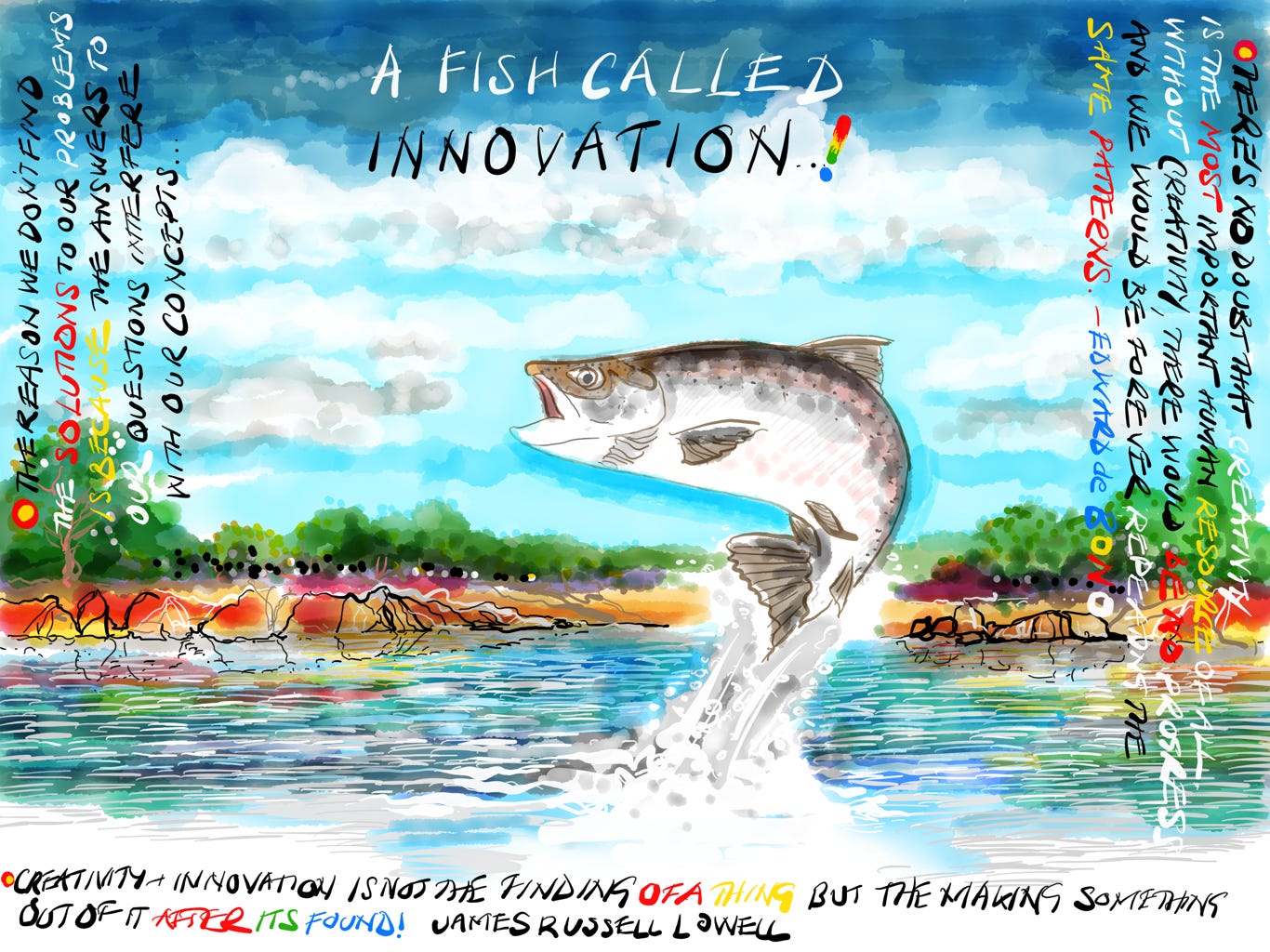

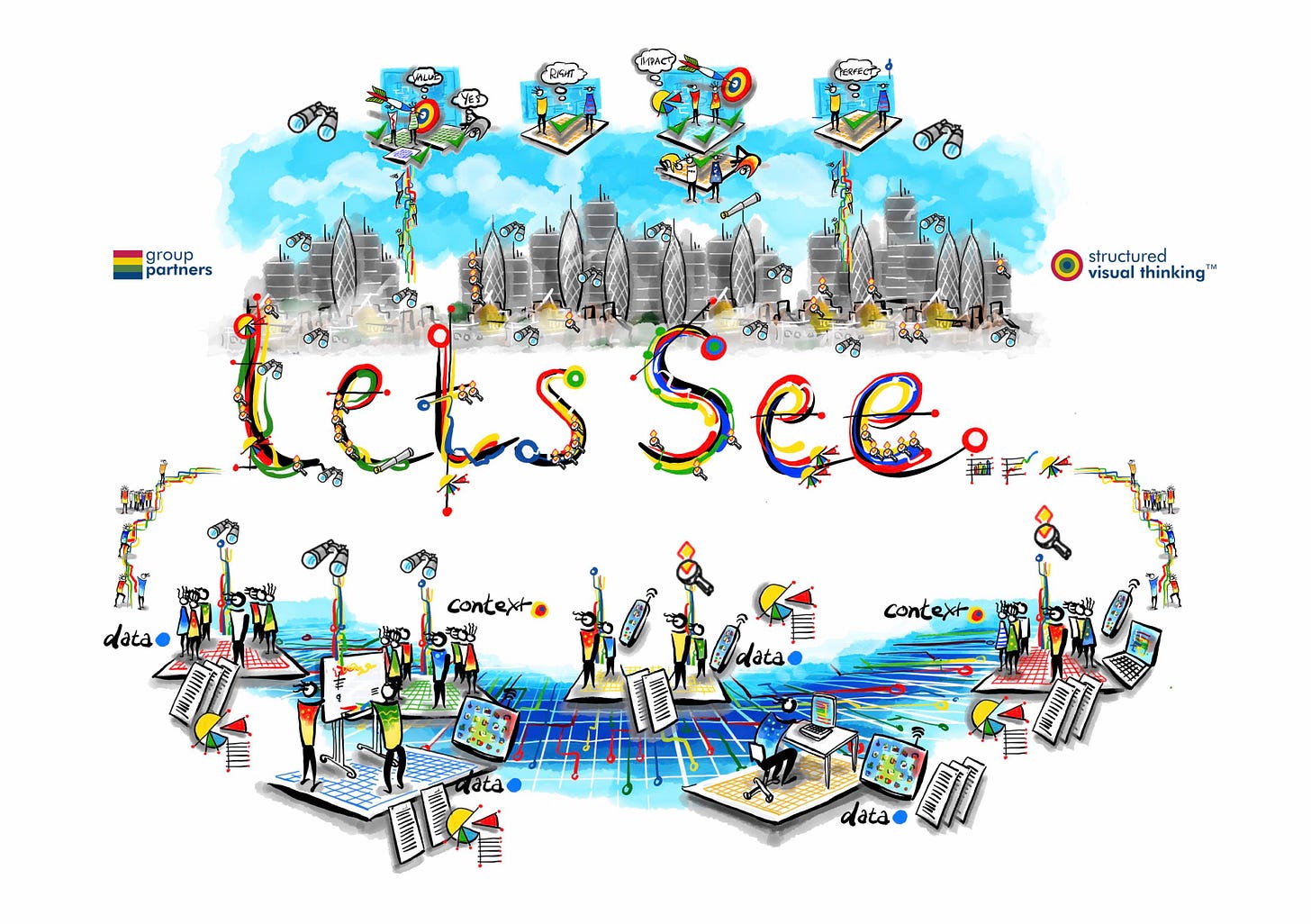

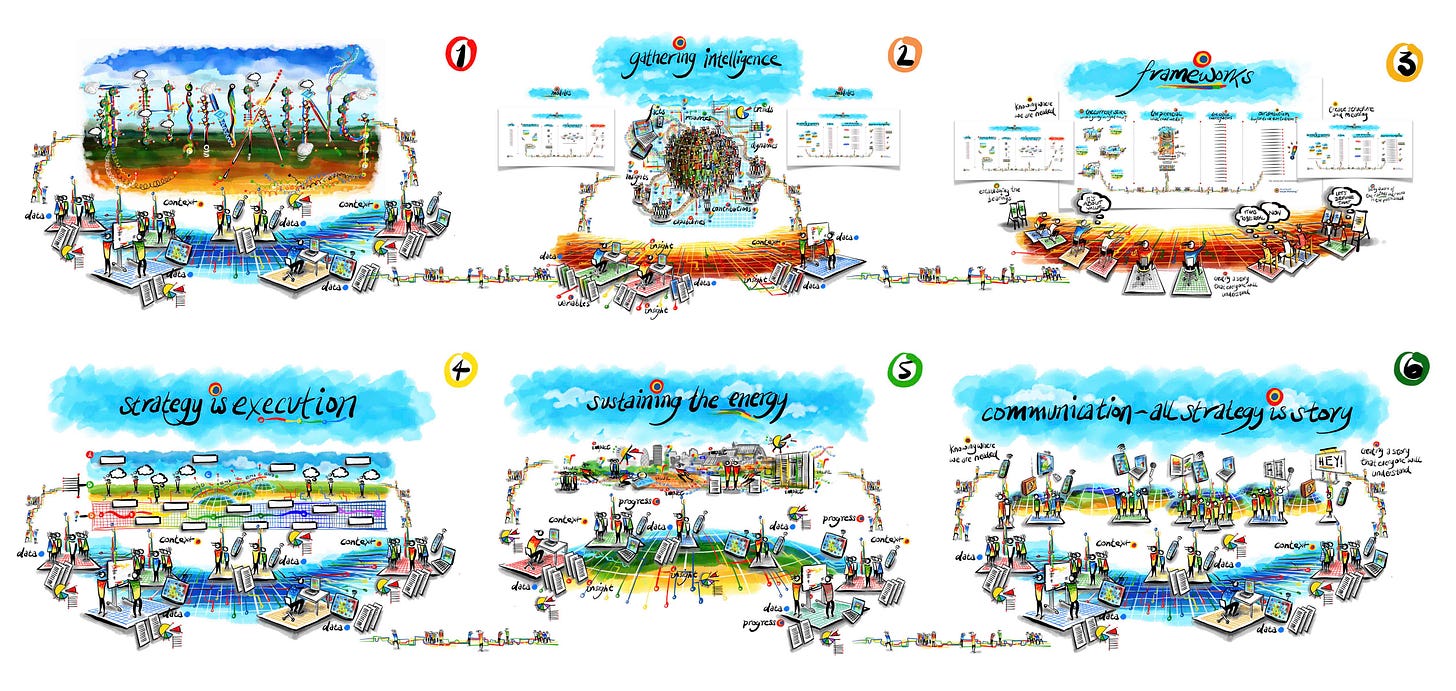

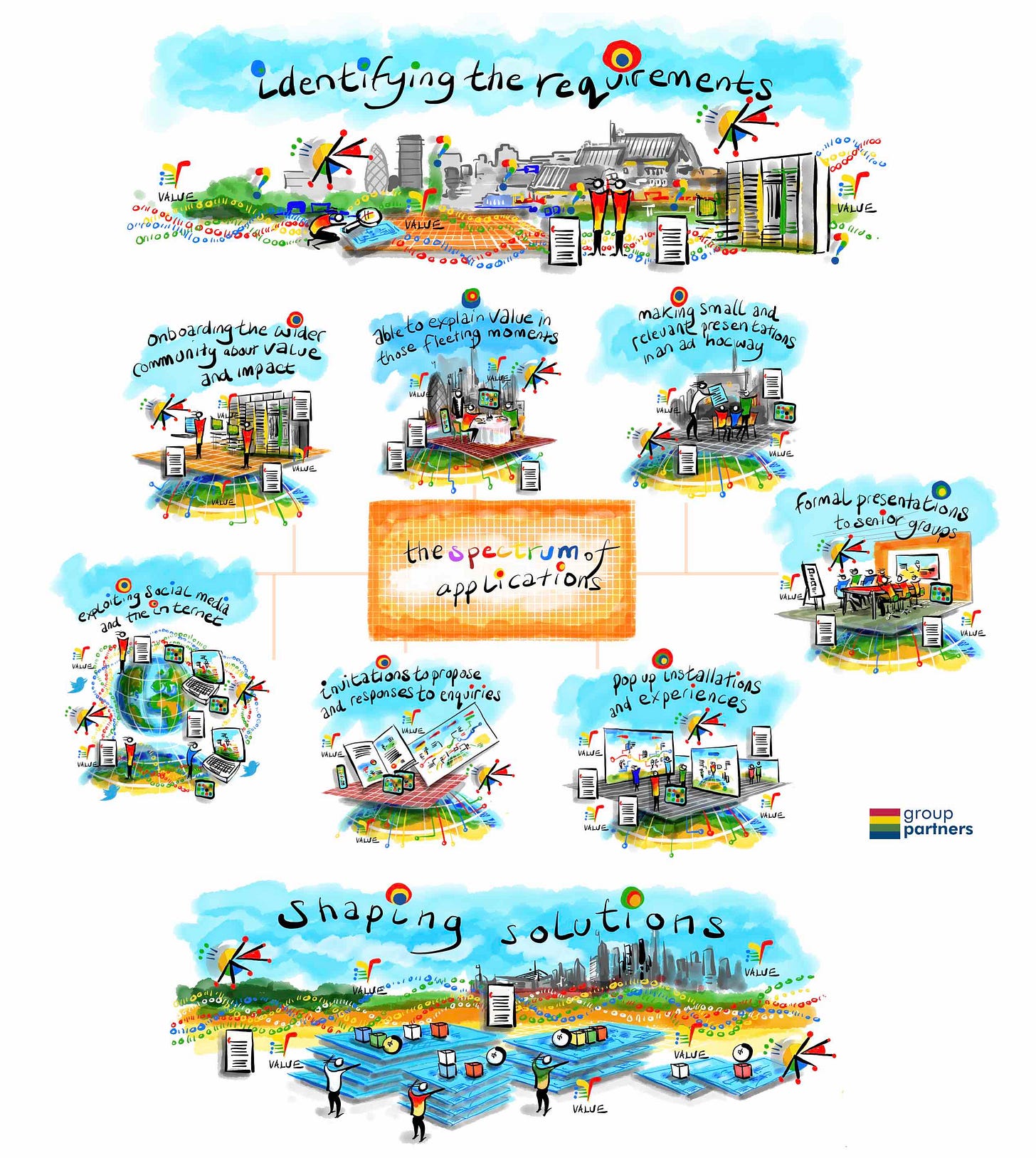

I peppered my original article with some hand drawn images. I've kept them in. They're old now (2017) but they gave me so many lessons AI could never have.

I brought the research up to date a bit.

What started out as a paper in praise of drawing as a powerful tool in the kit, has become a call to arms before we lose a superpower.

It's a long article. If I wasn't so concerned it might have been shorter.

The brain in your hands.

A provocation:

The hand hesitates. The algorithm doesn't. That hesitation is where every good idea lives. And every prompt is a thought you didn't have.

Humans stopping drawing is a biological catastrophe.

Here's a sentence I never thought I'd have to write.

We need to defend the act of drawing.

I don’t mean drawing as art or drawing as decoration but drawing as thinking. Drawing is a 65,000-year-old cognitive technology that helped make us human.

I worry that we are now rapidly (and casually) abandoning it because a machine can produce a picture faster.

Most people here won’t have missed how dire most AI art is. There are some notable exceptions. (Boesch)

I see dead, soulless, lazy, ignorant and pointless images everywhere. Prompts as felonies.

The Crime Wave

The internet is drowning in AI-generated images. I now unsubscribe from anyone or anything that complacently insults my intelligence.

Over 15 billion such ‘crimes’ have been committed since 2022.

Europol warns that up to 90% of online content may be synthetically generated by the end of 2026.

Deepfake files have surged from 500,000 in 2023 to a projected 8 million and beyond this year. (I fear that’s wildly conservative)

When everything can be faked, nothing can be believed. And trust me that’s not merely a tech problem but a catastrophe for civilisation.

Some 65,000 Years of Thinking With Marks

Buried beneath the sewage is something far more disturbing than bad taste. We are losing the capacity to think with our hands.

Cave paintings in Spain dating back 65,000 years weren't made by Homo sapiens. They were made by Neanderthals. The Max Planck Institute researchers who dated them concluded that Neanderthals and modern humans must have been cognitively indistinguishable.

Drawing, our impulse to make marks on surfaces, predates our species. It may be older than language itself. The significance of the paintings is that they were engaging in symbolism and almost certainly language.

My guess is that drawing preceded and probably enabled language. The mark came before the word.

I’ve said so repeatedly but for tens of thousands of years, every major leap in human understanding has started as a drawing.

Maps traced in sand. Euclid's geometric proofs. Leonardo's anatomical sketches. Darwin's tree of life. The periodic table. The double helix. The circuit board. Each began as marks on a surface, someone wrestling an idea into visible existence with their hand.

And now we're outsourcing that to algorithms.

The Brain That Draws Is a Different Brain

The science (neuroscience) gets uncomfortable for anyone who thinks AI-generated images are ‘good enough.’ I know it’s fashionable (stupid) to deny science these days. But fuck that.

And I’ve collected many facts on the power of visualisation over the years and here’s some new and timely research. A few fascinating insights.

These will impress your friends.

I recently got sent a meta-analysis published in the journal Cerebral Cortex. It found that drawing activates a fronto-parietal network unlike any other motor activity.

It's not the same as typing. It's not the same as tapping a screen. The left inferior parietal lobe, the region responsible for combining single elements into integrated wholes, it lights up specifically during drawing.

Think of it as the part of the brain that does the synthesis. It's where ‘parts’ become meaning.

A 2021 longitudinal study published in Neurobiology of Learning and Memory tracked art students over a 16-week observational drawing course.

“The results showed significant brain plasticity, enhanced functional connectivity within and between the cerebellar, default mode, and salience networks. These are the regions responsible for complex motor coordination, cognitive processing, and attentional control. Drawing didn't just use their brains differently. It changed their brains.”

Research from Art UK's neuroaesthetics review put it quite plainly -

"Drawing is a process by which the brain transforms perceptions into actions, and in doing so, it enhances the brain's ability to share information and think critically."

And then there's memory.

Jeffrey Wammes and Myra Fernandes at the University of Waterloo demonstrated (across seven separate experiments) what they call ‘the drawing effect’.

People who drew the information they were trying to remember recalled more than twice as much as those who wrote the words down. The effect held up even when drawing time was cut short. Even when the drawing quality was poor or the information was abstract.

The mechanism?

Drawing integrates semantic, visual, and motor codes into a single, rich memory trace that no other encoding method can match.

The benefit was as large or larger in older adults as in younger ones, drawing tapped into preserved visual and motor systems that other memory strategies couldn't reach.

The hand doesn't just record what the brain knows. The hand helps the brain know.

The Slop Machine

“AI slop isn't bad art. It's the absence of art occupying art's space. Visual landfill marketed as content.”

Now set all that against what's actually happening in the world.

Recent data told me that:

As of late 2025, over half of all newly published English-language articles online are primarily AI-generated.

AI content in Google search results has climbed to nearly 20%.

State-sponsored propaganda campaigns have embraced generative AI to flood the internet with synthetic content, images, videos, text, and fake personas, at industrial scale.

The term ‘AI slop’ (untreated sewage) has entered the language. Wikipedia now has a page for it.

YouTube's CEO declared reducing slop and detecting deepfakes a priority for 2026.

The UK government has called deepfakes ‘arguably the greatest challenge of the online age’ and declared tackling them an urgent national priority.

Fraud attempts using deepfakes have increased 2,137% over the last three years. Human detection rates for high-quality deepfake video sit at just 24.5%, worse than flipping a coin.

A 2025 iProov study found that only 0.1% of people could correctly identify all fake and real media shown to them.

Here's a punchline no one should live with

60% of people believe they can spot a deepfake. Virtually none of them actually can.

We are engineering a world where the visual environment is polluted beyond recognition, and simultaneously abandoning the one cognitive skill that teaches us to look properly.

What Drawing Teaches That Nothing Else Can

I don’t care about the quality. It can be a stick figure. When you draw something, you have to commit. Not a casual glance or two. Not a scroll or scan.

A bad drawing is evidence of a mind at work. A perfect render is evidence of nothing.

You have to understand the structure you want well enough in your mind's eye, (imagination) to reconstruct it with your hand on a surface. This is a fundamentally different act from selecting an image from a menu, choosing from AI outputs, or typing a prompt.

Stanford neuroscientist Judy Fan, whose Cognitive Tools Lab studies drawing as a fundamental human cognitive skill, puts it this way.

“People who practise drawing aren't seeing objects differently, they're getting better at communicating what makes the thing that thing to their hand. They're getting in tune with essential nature. The sensory brain and the motor brain are learning to speak to each other.”

That feedback loop, eye to hand to surface and back to eye again, is irreplaceable. It's slow. It's imperfect. It's inefficient. And those are exactly the qualities that make it powerful.

Because drawing forces you to stay with the problem. You can't skip the gap between what you intended and what appeared. That gap is where insight lives.

AI-generated images eliminate that gap entirely. They give you a destination without a journey. And the journey was always the point.

The Generation That Never Draws

That catastrophe is awaiting us.

We already know that around 30% of ‘typically’ developing children have difficulty learning handwriting.

Research published in Life journal shows that children who don't develop handwriting skills may miss the precise hand movements needed for drawing, cutting, or any task requiring fine motor coordination.

The shift toward typing in early education prioritises speed and efficiency over deep learning and cognitive engagement.

What happens to a generation that never draws at all? Not ‘can't draw well’ or never draws. Never experience the feedback loop between hand and eye and idea.

“A generation that never wrestles an image into existence from nothing. Never discovers what they think by watching what their hand does.”

We're not automating drawing. We're automating the decision not to think.

We're losing a thinking pathway.

And unlike a muscle that atrophies but can be rebuilt, a cognitive pathway that never forms in the first place leaves no trace of what was missed. A generation learning to select rather than create.

The brain treats drawing as rewarding.

The pleasure you feel when a line lands right, when a shape emerges from nothing, when the thing on the paper starts to look like the thing in your mind. That's a joy.

It's also a biological indicator that deep processing is underway. There's a thrill no matter the quality of the drawing.

The Radical Act of Picking Up a Pen

So here we are. The internet is drowning in synthetic images. Trust in what we see is collapsing. Deepfake fraud is projected to cause $40 billion in losses by 2027. And the educational response is to put children in front of screens earlier and for longer.

Picking up a pen and drawing is now a radical act. If you've read this far you probably feel there's something at risk here.

“Drawing is slow in a world optimised for speed. It's imperfect in a world that demands polish. It's individual in a world that scales everything. It requires you to think at the speed of your hand, not at the speed of an algorithm. It insists that you stay with the problem, look properly, and make something that didn't exist before through the unique partnership between your brain and your hand.”

No machine can replicate that partnership. No prompt can be a substitute for the cognitive loop between eye, hand, surface, and idea.

No amount of AI-generated imagery can replace the thinking that happens when you draw.

Every child who never picks up a pencil to draw is a mind that never fully learns to see. Every adult who stops drawing because ‘AI does it better’ is surrendering a cognitive capability that took 65,000 years to develop in exchange for convenience.

Draw something today. Anything. Badly, it doesn't matter. Your brain will thank you.

Fab @JohnCaswell « The hand hesitates. The algorithm doesn't. That hesitation is where every good idea lives. And every prompt is a thought you didn't have. » This is it 👆🏻

Despite all the attempts to embody AI, we forget that courageous leaders doubt too and that is far too wide boundaried thinking and doing for the narrow AI we have. #plurality #artandscience #imagination

Always drew as a child, and found it to be a wonderful way of exploring thought. Too much time on the keyboard now, which is also great for communication, reading and sharing to promote conversations and connections, much like this! Thanks.